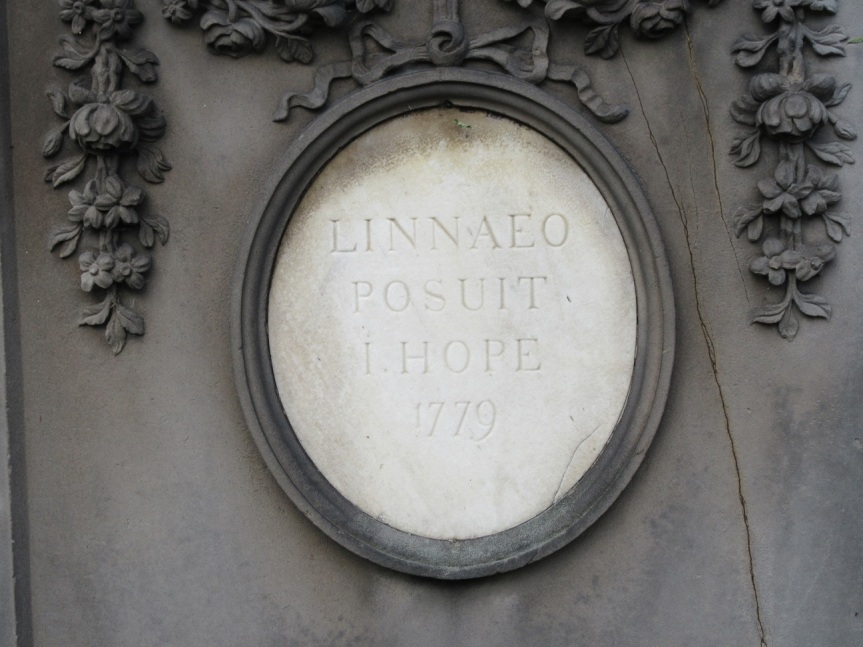

I was at the Botanical Gardens last weekend, originally because I’d read that there was an 18th century monument there to Linnaeus, and I was sure I had never seen it – for good reason, it turns out, because it’s hidden round the back of the greenhouses in what seems to be a rather dreary packed lunch area.

It’s shown on the maps of the gardens, and then as you head towards the education building a sign tells you that the ramp takes you to it – but the ramp was roped off at both ends and marked as being for school parties only, so I had to do some surreptitious clambering – and then ended up inside the paying area of the greenhouses, which I felt a bit guilty about.

John Hope was Regius Keeper of the gardens, and responsible for establishing the gardens in their previous site on Leith Walk (where the monument presumably started out), as well as Professor of Medicine and Botany at the University of Edinburgh.

I feel like writing to the RBGE to complain about their neglect – this seems to be one of the oldest monuments in Edinburgh – but I’d have to admit to the trespassing, so maybe I won’t!

Anyway, I was then reminded of an even older and more exciting thing – both the oldest and the newest building in the gardens, as they describe it – the Botanic Cottage.

Built in 1764, the year after the site was bought for the gardens on Leith walk, this was the entrance to the gardens for visitors – on what was then a country road running from the town of Edinburgh to the town of Leith – as well as the home of the head gardener (downstairs), and a classroom where medical students were taught botany during the Scottish Enlightenment (upstairs).

Over the years, and after the gardens moved to Inverleith in 1822, Leith Walk was built up around the cottage, the road being raised to level with the first floor, and one end being removed to build a block of flats. Eventually it was to be demolished, but instead it was carefully taken to bits, and rebuilt and recreated in the current gardens.

Over one of the side entrance gates is a plaque to John Williamson, head gardener at the time the cottage was built, who also worked as a customs officer and was killed by smugglers in 1780.